The social media landscape has, once again, been embroiled over the issues of free speech and ‘cancel culture’ this month following Harper’s open letter titled “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate”.

The letter, signed by over 150 writers, journalists, historians and other prominent figures, includes Noam Chomsky, JK Rowling, Salman Rushdie and Margaret Atwood, among others, and vaguely addresses and condemns “a new set of moral attitudes and political commitments that tend to weaken our norms of open debate and toleration of differences in favour of ideological conformity”.

Almost in the same breath, one such signatory Bari Weiss, now former New York Times opinion writer and editor, also announced her resignation from the publication citing issues around internal censorship, claims of workplace harassment, and the ever-increasing significance that social media now plays in the editorial process in a letter of her own: “Twitter is not on the masthead of the New York Times. But Twitter has become its ultimate editor. As the ethics and mores of that platform have become those of the paper, the paper itself has increasingly become a kind of performance space. Stories are chosen and told in a way to satisfy the narrowest of audiences, rather than to allow a curious public to read about the world and then draw their own conclusions.”

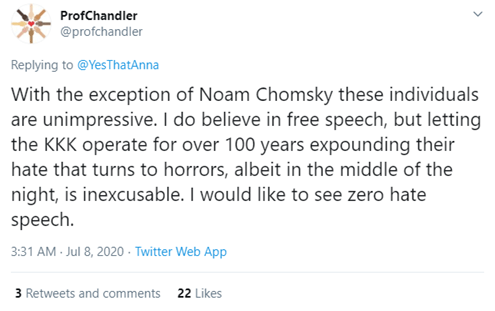

The subsequent reaction to both pieces on social media has been varied, from enthusiastic agreement, to cynical scepticism, to absolute outrage. Those who agree ultimately laud the right to freedom of speech from all sides of the political spectrum, with the inclusion of Chomsky particularly notable in this instance; he himself notes his experiences with his books being withdrawn from publication, or destroyed, due to their contents, as well as the forced elimination of faculty positions of those around him.

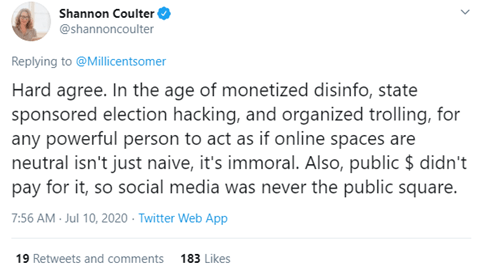

Conversely, those with concerns question how far we can realistically allow this freedom of expression, ideology, and discourse in social media spaces before it becomes harmful or potential damaging. As well, when should the spread of what may be deemed harmful discourse be punished, and to what degree?

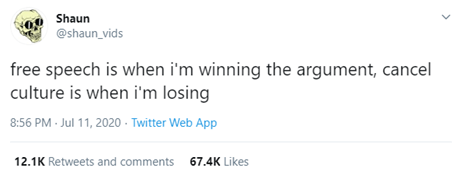

The most pertinent point of outrage concerns the idea that, in many instances, ‘cancel culture’ is merely the name given when a majority, or a large audience, simply disagrees with your idea, as opposed to suffering from any real action taken; Rowling in particular writes that “I must have been on my fourth or fifth cancellation” by now in relation to her various statements regarding trans issues. Amid both Black Lives Matter protests and a raging global pandemic, it may also be easy to consider the letter as a clumsy attempt for certain high-profile figures to express their frustrations with public backlash and scrutiny, despite its vagueness but general sincerity.

The instigator of the Harper’s letter, writer Thomas Chatterton Williams, told the New York Times that those on the list are: “…not just a bunch of old white guys sitting around writing this letter. It includes plenty of Black thinkers, Muslim thinkers, Jewish thinkers, people who are trans and gay, old and young, right wing and left wing. We believe these are values that are widespread and shared, and we wanted the list to reflect that.”

However, at a time where social media is now expected to address false news and #StopHateForProfit, does the Harper’s letter do enough to address the ever-growing sphere of disinformation and animosity-fuelled environments of public dialogue?